Multi-Class Basketball May Have Saved Indiana Basketball

Matthew A. Werner & Richard J. Penlesky

It’s been 25 years since single-class Indiana high school basketball was last played (1997), yet some Hoosiers still pine for its return. Curmudgeons claim that multi-class sports ruined Indiana high school basketball and they cite falling tournament attendance as evidence. Nobody has dug deep into the history and the data of class basketball. Until now. It turns out, multi-class basketball may have saved Indiana basketball.

Background

In 1996, 100 Indiana High School Athletic Association (IHSAA) member schools submitted a petition to start multi-class athletic tournaments for most sports, including basketball. The board of directors voted 12 – 5 to implement this suggestion, and a referendum vote of all member schools followed. Members voted 220 – 157 in favor of a multi-class tournament to begin in the 1997-98 school year.

So, multi-class basketball began and so did the voices clamoring to return it to the way it was. The clamorers’ pitch peaked in 2012. That year, a state legislator, Mike Delph, added language to a bill that would make it illegal for any Indiana high school to participate in a multi-class basketball tournament. The IHSAA agreed to participate in 11 town halls around Indiana to hear Hoosiers’ opinions of multi-class basketball. A straw poll was taken at each stop. Most Hoosiers ignored the spectacle. Only 514 people cast ballots at these events; of these, 350 voted for a return to a single-class tournament.

Then the IHSAA polled member schools. Every group—principals, athletic directors, basketball coaches, and student-athletes—voted overwhelmingly to stick with multi-class basketball. The votes tallied 5,181 (71.6%) in favor of multi-class sports and 2,055 (28.4%) against. Multi-class sports remained.

Nevertheless, week by week, month by month, year by year, lamenters lamented multi-class basketball. They wrote newspaper editorials, called into local sports radio, and complained every time they had a captive audience. Social media posts filled with their grievances. Some sportswriters have joined in to elevate these voices. Most complaints contain a fatal flaw—they do not reflect any further back than 1990. We will not make that mistake here.

Some History

Basketball has been a popular activity in Indiana since its arrival to the state in the 1890s. Shortridge High School girls assembled a team in 1898 and a statewide high school tournament for boys started in 1911. The boys tournament grew from 12 teams in 1911 to a peak of 787 teams in 1938.

In the early years of the state tournament, small schools occasionally appeared in the state championship game (Montmorenci, 1915; Winamac, 1932; Mitchell, 1940; Madison, 1949) and even won it all (Wingate, 1913 and 1914; Thorntown, 1915; Madison, 1950; Milan, 1954).

Over time, the game progressed. Two significant changes to the game were the elimination of a center jump after each made basket (1937) and adoption of the jump shot[1]. Basketball got faster and athleticism gave players and teams a greater advantage than before. When Bob Plump of Milan High School made his famous jump shot to win state in 1954, most Hoosier high schoolers had never taken a jump shot—set shots, hook shots, and push shots were the norm.

Unbeknownst to most people, Hoosiers called for a multiple class state basketball tournament in the 1940s and 50s. For instance, in 1950, Tippecanoe High School Coach Ray Bevington proposed the winner of four classes, based on enrollment, advance to the State championship to give small schools a better chance of winning[2].

When Milan High School (164 enrolled students) went to the final four in 1953 and then won state in 1954, it was a made-for-media love affair and Hoosiers fawned over their feat.

The Milan Miracle silenced voices calling for a multi-class tournament. However, the miracle marked the end of an era. While the first 43 years of the Indiana high school basketball tournament witnessed the occasional small school in the championship game, the next 44 years saw no school with fewer than 894 students[3] win State (Plymouth, 1982) and only one high school ranked in the bottom half by enrollment (Loogootee, 1975) reached the championship game, and lost.

Numbers Tell A Story

In the years following World War II, the number of tickets sold to the statewide basketball tournament rose from 1,157,451 in 1946 to 1,554,454 in 1962. It seemed you couldn’t build a gymnasium big enough to seat all of the people who wanted to attend, so schools built larger and larger gyms. Elkhart built a 7,300 seat gym in 1954, Southport built a 7,100 seater in 1958, the largest high school gym in the country was built in New Castle in 1959, and the Anderson Wigwam, which sat 9,000 fans, opened in 1961.

However, tournament attendance peaked in 1962. After that, fewer and fewer people attended the four rounds of the boys state basketball tournament: sectional, regional, semi-state, and state.

A scapegoat for this downward trend could be the School Consolidation Act of 1959. It reduced the number of school districts from 966 to 402[4]. It also reduced the number of high schools participating in the state basketball tournament from 710 teams in 1959 to 660 in 1962, 427 in 1972, 395 in 1982, 383 in 1992, and 382 in 1997.

While the bulk of high school consolidation (84%) had occurred by 1972, basketball tournament attendance continued to fall:

- 1962: 1,554,454

- 1972: 1,332,675

- 1982: 1,076,886

- 1992: 861,124

- 1997: 786,024

As attendance declined, giant gymnasiums continued to be built:

- 1966: Washington, 7,000 seats

- 1969: Lafayette, 7,200; Gary West Side, 7,200

- 1970: Marion, 7,600; Seymour, 8,200

- 1971: Michigan City, 7,300

- 1984: Richmond, 7,800

- 1988: East Chicago, 7,800

But tumbling attendance in growing gymnasiums is not how people remember it. On a Facebook group dedicated to Indiana high school basketball fans, a man wrote that the New Castle gym was full every sectional up until the switch to multi-class basketball—then and only then did attendance collapse. He knew, he assured everyone, because he was there!

That is a common refrain, but nostalgia has a way of rosying the lens through which we see the past. In 1997—the last year of single-class basketball—10,475 people attended the three sessions of the New Castle Sectional. That means attendance was 38% of total seating capacity. When confronted with the facts, the man doubled down, insisting that the IHSAA official figures were wrong and he was right.

Official sectional ticket sales and the percent of seating capacity filled in the 1997 boys basketball tournament at the other largest Indiana gyms were as follows:

| Gym | ’97 Total Attendance | Percent of Capacity[5] |

| Anderson | 17,214 | 64% |

| Marion | 13,238 | 58% |

| Elkhart | 13,239 | 51% |

| Seymour | 10,923 | 45% |

| Lafayette Jeff | 9,362 | 43% |

| Richmond | 7,665 | 32% |

| Michigan City | 6,516 | 30% |

| Gary West Side | 4,566 | 21% |

| East Chicago | 4,828 | 19% |

| Southport | 1,831 | 13% |

Hoosiers did turn out in large numbers to see top players and top teams. In 1988, superstars Shawn Kemp (Elkhart Concord) and Damon Bailey (Bedford North Lawrence) led their teams to the state tournament final four. Two years later, the Elkhart and Seymour Sectionals were at 96% capacity as fans watched the two teams return to the state finals. That year, the final four was moved from Market Square Arena (which had sold out 17,000 seats from 1975 to 1989) to the Hoosier Dome, home of the Indianapolis Colts professional football team.

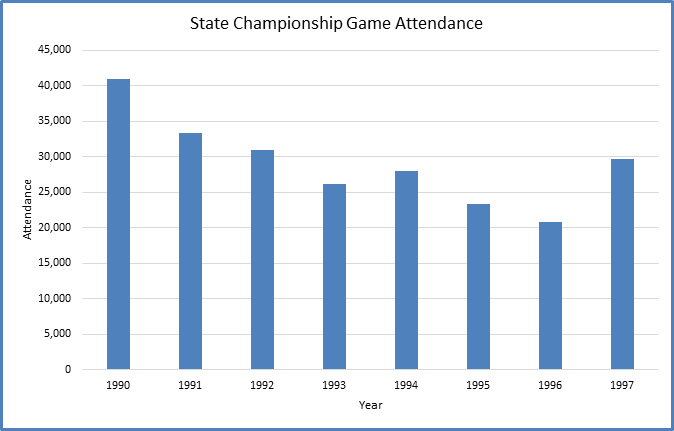

Everyone remembered that 41,046 fans watched Elkhart Concord and Bedford North Lawrence play head-to-head in the state championship game in 1990. Nobody remembered that nearly half as many people attended the Ben Davis vs. New Albany championship game in 1996 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Indiana High School Athletic Association (IHSAA) data.

How could our memories deceive us? Experts have known for years that our memories are not accurate. One explanation is peak-end theory, whereby people tend to remember the most intense moments and the last moment of an event. Therefore, we recall the moments the gym was full and forget the times when it was half-empty. Another explanation is rosy retrospection, whereby we judge the past more positively than we do the present. Or it could be simple nostalgia. Regardless the reason, we tend to remember things as better than they were. Rather than rely on imperfect recollections, we collected data to study relationships between tournament attendance and tournament class format.

A Deeper Dive into the Data

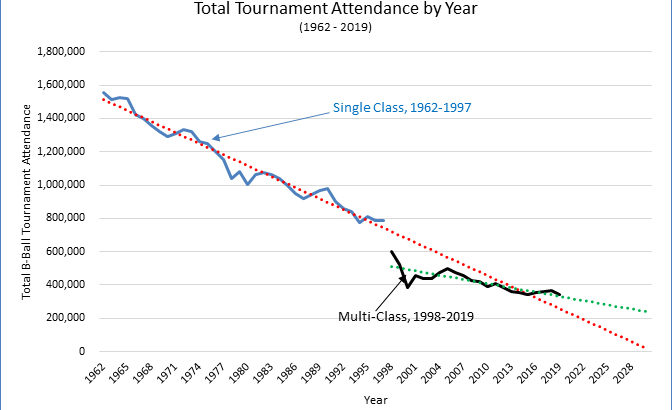

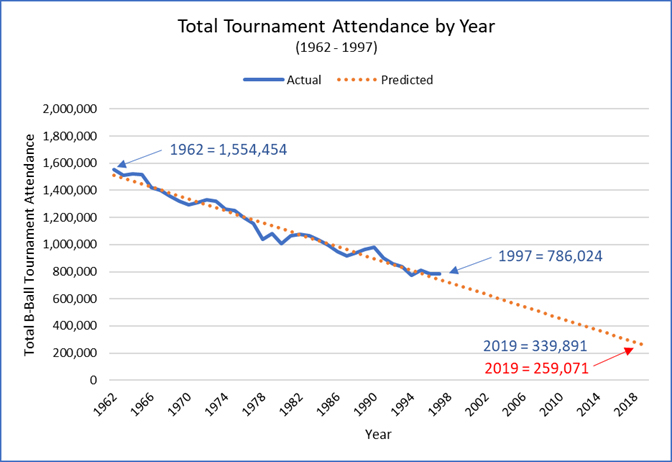

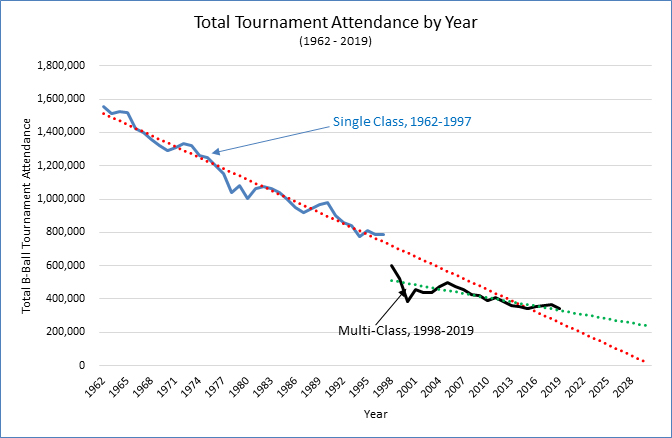

To start, we analyzed total tournament attendance by year under the single-class format (1962 to 1997). This data is represented by the solid blue line in the graph in Figure 2. The graph demonstrates that tournament attendance declined dramatically during this 35-year period. The dotted red line in the graph represents a trend line (least squares regression) that irons out the random fluctuations during the 35 years of single-class tournaments and projects future attendance (ceteris paribus) if the tournament format remained unchanged.

The projected single-class attendance in 2019 was 259,071. The actual attendance—under the multi-class format—was 339,891. Total attendance at the 2019 tournament was 31% higher under the multi-class format than it likely would have been under the single-class format.

Figure 2. IHSAA data.

Next, we analyzed total tournament attendance by year under the multi-class format (1998 to 2019). It is represented by a solid black line in the graph in Figure 3. When the trend line is added to this data (dotted green line), it becomes clear that the declining slope of the multi-class trend line is not as steep as that of the single-class trend line. Although the multi-class tournament did not cause attendance to increase, it significantly slowed the rate of attendance decline. As a result, multi-class basketball may have saved Indiana basketball.

Figure 3. IHSAA data.

What Did Cause Attendance to Drop?

So, if multi-class basketball isn’t responsible for attendance decline, what is? Three factors stood out: the number of IHSAA sanctioned sports, the number of high school boys basketball players, and the number of girls participating in high school sports.

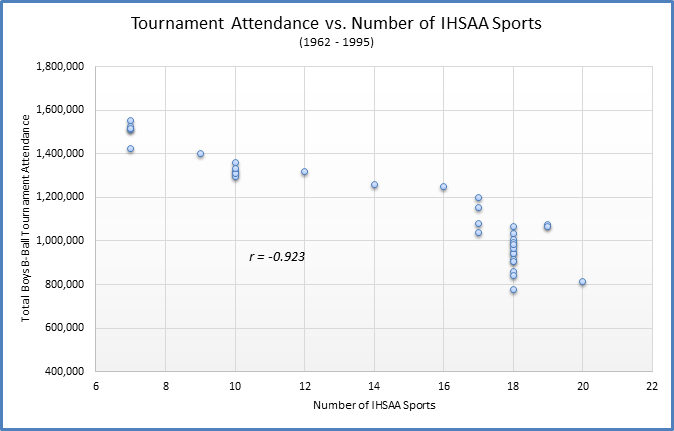

In 1962, the IHSAA sponsored seven sports—all for boys. There were no sports for high school girls to play in Indiana. Since 1995, the IHSAA has sanctioned 20 sports—10 for boys and 10 for girls. The relationship between total boys basketball tournament attendance and number of IHSAA sports over the period from 1962 to 1995 is shown in the scatter graph in Figure 4.

Figure 4. IHSAA data.

There are 34 points on the graph—one for each combination of total basketball tournament attendance and the number of IHSAA sponsored sports that year (1962 to 1995). The correlation between the two data sets is strong (r = -0.923). The graph shows that total basketball tournament attendance declined as the total number of sports increased.

More sports meant more student-athletes playing more games in a greater variety of sports. This is a good thing. An unintended consequence is that it may have contributed to the attendance decline at the boys high school basketball tournament.

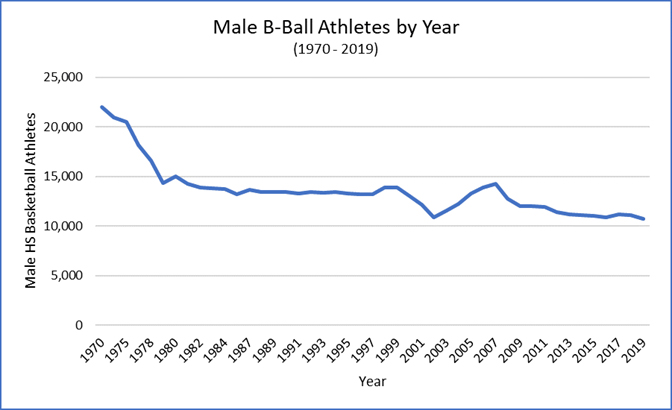

As mentioned earlier, the School Consolidation Act reduced the number of high schools participating in the statewide boys basketball tournament from 710 teams in 1959 to 382 teams in 1997. Fewer high schools meant fewer boys basketball teams, fewer boys basketball players and, most likely, fewer boys basketball fans. Whereas there were 21,983 male high school basketball players in 1970 (the earliest year for which data was available), there were 13,722 male basketball players in 1984 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) data.

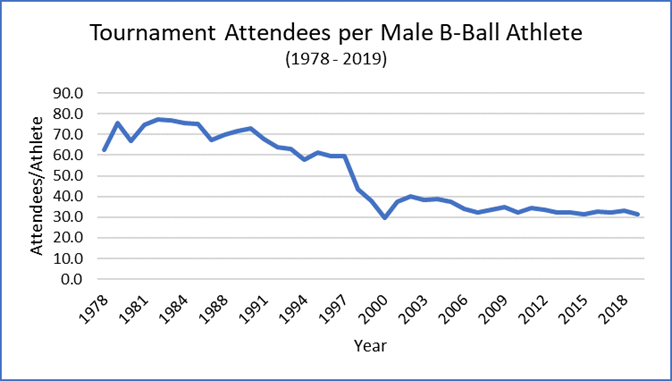

In the early years of school consolidation, fans of boys basketball seemed to hang around, as indicated by the number of basketball tournament attendees per male basketball player. This ratio peaked in 1982. Afterward, the number of boys basketball tournament fans per male basketball player declined for the next 18 years; the ratio hit bottom in 2000 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. IHSAA and NFHS data.

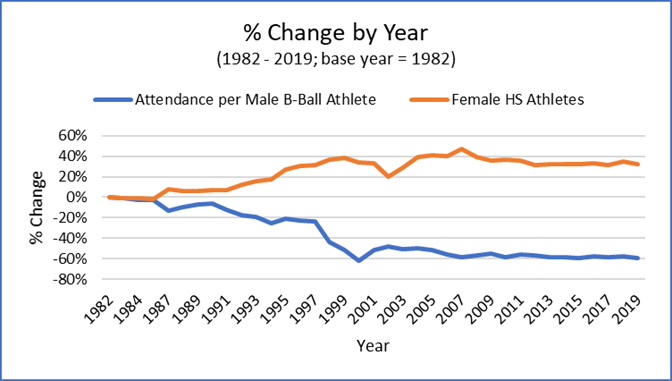

This relationship leads us to the third factor that affected attendance: number of girls participating in sports. The precipitous decrease in the number of tournament attendees per male basketball athlete corresponded with a dramatic increase in the number of female athletes. Whereas the number of tournament attendees per male basketball athlete decreased 62%, the total number of female athletes increased 34% from 1982 to 2000 (see Figure 7)[6].

Figure 7. IHSAA and NFHS data.

The year 1984 marked an important point in Indiana high school athletics—it was the first year that the IHSAA offered an equal number of sports for boys and girls. Before that, boys always had more sports to play than girls. This equality was a result of the Title IX Education Amendment in 1972 that prohibited sex-based discrimination in schools. In 1972, the IHSAA offered zero sports for girls and 10 sports for boys. It took 4 years for the IHSAA to recognize girls basketball and 12 years to have an equal number of sports for girls as boys. Subsequently, the number of girls participating in high school sports increased. This also is a good thing.

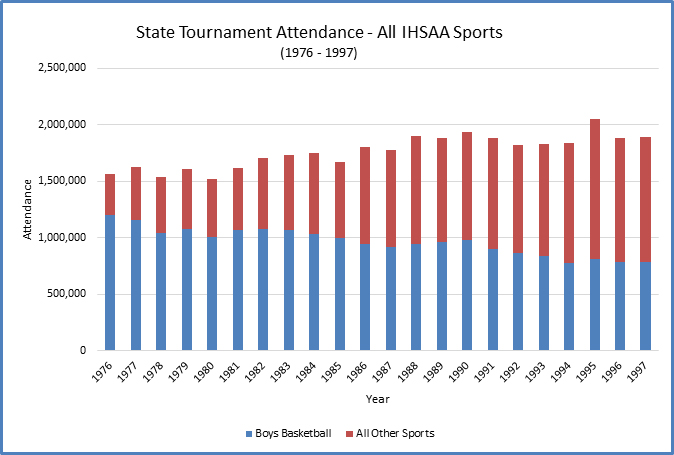

While the number of boys basketball tournament attendees declined, the total number of people who attended all IHSAA tournament events, boys and girls, rose steadily (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. IHSAA data.

These three factors—more sports, fewer male basketball players, and more female athletes—have strong statistical relationships to declining boys basketball tournament attendance. It is likely that, in addition to these factors, various changes in Hoosiers’ lives over the last 60 years contributed in small ways as well.

There are more dual-income families. People work more hours and travel further to get to work. Families have more cars per household. There are more entertainment outlets and creative outlets for kids and adults on which to spend dwindling free time. There are more televisions per household, more TV channels, more broadcast sports, and high-definition TV. Travel sports teams and video games have proliferated. Internet access has climbed from 18% of households in 1997 to 78% in 2018. 84% of households have a smart phone. Social media has opened new avenues for people to interact.

A return to single-class basketball would not bring back the tournament people remember from the past. For that to happen, we would need to reverse all of the things that have changed in our lives between then and now.

The switch to multi-class basketball did not significantly change Indiana high school basketball. Instead, it amplified our awareness of how much the world around us has changed. It shocked our systems and led some people to swear off Indiana high school basketball and the statewide tournament. Meanwhile, Indiana basketball continued to be played at a high level.

Indiana Basketball Remains at High Level

In the 2016-17 season, there were 17 Hoosiers playing NBA basketball. That put Indiana number 4 on the list of states with the most NBA players behind California, Texas, and New York—three of the largest states in the country. Indiana is 17th in population.

In 2018, basketball fans filled every gym in which Romeo Langford and his New Albany High School teammates played in the tournament, eager to see if the boys could repeat their 2016 title run.

From 2007 to 2021, Indiana averaged 3.53 high school basketball recruits on ESPN’s top 100 list. This is 3.53% of recruits over that time period while Indiana makes up only 2% of the U.S. population.

If Indiana’s status as a premium basketball hub had faltered, the Indiana – Kentucky All Star game series would provide an indication. They have played 145 times since 1940. From 1940 to 1997, Indiana All Stars won 61 games and Kentucky All Stars won 38; that’s a 62% Hoosier winning percentage. Under the era of multi-class basketball in Indiana, 1998 to 2021, Indiana won 40 games while Kentucky won 6. That’s 87%. Ironically, Kentucky maintains a single-class state basketball tournament today.

The men and women who played Indiana high school basketball over the last 25 years in the multi-class tournament fought and clawed and played to win. They sweated, and bled, and cried, and cheered. They hoisted trophies and suffered defeat just like everybody before them. Today’s tournament is not better, or worse—it’s just different.

If you preferred single-class basketball, so be it. Nobody can begrudge you. But don’t say multi-class basketball ruined Indiana basketball—we know that’s a myth.

Indiana basketball lives on.

————————————————————————————–

[1] Davage Minor of Gary Froebel H.S. is credited as the first Hoosier to take a jump shot. He led his team to the state final four in 1941. The jump shot did not garner widespread use until the second half of the 1950s.

[2] LaPorte Herald-Argus, February 18, 1950.

[3] Krider, Dave. Indiana High School Basketball’s 20 Most Dominant Players, p 215. 2007. Plymouth High School won State in 1982 and had total enrollment of 894 students. That placed the school among the largest 30% of all high schools in Indiana.

[4] School Reorganization Commission Collection, Indiana State Library. https://www.in.gov/library/files/L591_School_Reorganization_Commission_Collection.pdf

[5] Percent of Capacity = Attendance ÷ (Gym’s Seating Capacity x Number of Sessions). Each location held three sessions that year except Southport, which held two sessions.

[6] Over the time interval from 1982 to 2000, these two variables are strongly and inversely correlated (r = -0.894). This correlation coefficient yields a coefficient of determination (r2) which suggests that 80% of the variation in attendance per athlete can be explained by variation in the number of female athletes. Therefore, from 1982 to 2000, the number of female athletes was a very good predictor of tournament attendance per male HS basketball athlete.