In LaPorte County, Indiana, there is a giant granite rock with bronze plaques on two sides dedicated to the Door Village Fort. As the story went, Chief Black Hawk was on the warpath, he and his warriors were murdering white settlers, and headed toward LaPorte. In response, noble pioneers banded together and constructed a fort in just three days to protect the good people from the marauders. Local children learned that story for a century. However, Black Hawk was not headed toward Indiana or murdering innocent settlers. The fort arose from a panic based on misinformation and hatred of Native American people.1Wyman, Mark. The Wisconsin Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 146. “The outbreak was created from many strands, including white pressure on lands, and Indian resistance; tribal divisions, and strife between tribes. But the major cause of the Black Hawk War was the long-term buildup of fear and hatred between Indians and whites along the Mississippi.” (Click superscript numbers to view interesting notes) That panic launched the Black Hawk War, an ugly stain on American history.

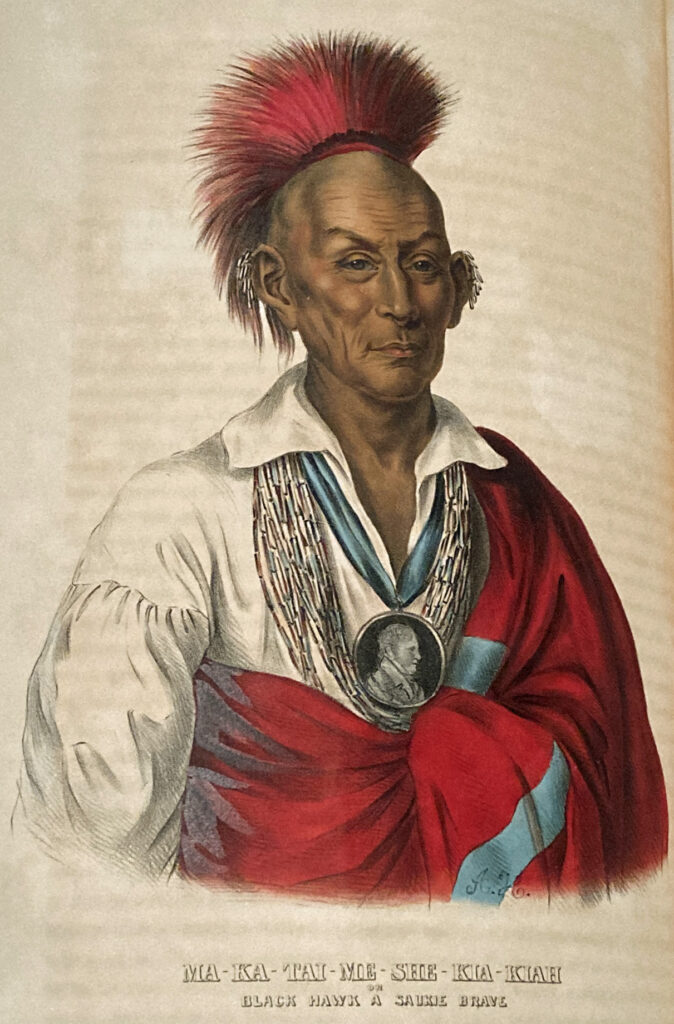

Black Hawk

U.S. government leaders, state government officials, and settlers forced most Native Americans from their homes in Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana beginning in the early 1820s. When Sauk tribes returned from their winter hunt to their hometown of Saukenuk (present-day Rock Island, Illinois) in spring 1829, they found their houses and fences destroyed and white settler’s cattle grazing in their fields.[2](Click parenthetical number to go to bibliography, not that interesting) Pressured by the United States government, Chief Keokuk led a large contingent of Sauk and Fox people from their ancestral homeland of Saukenuk across the Mississippi River and into the Iowa territory in Fall 1829. He vowed never to travel east across the Mississippi River again, which pleased U.S. government officials and settlers alike. Not all Sauk and Fox people agreed with Keokuk’s approach.

Born in Saukenuk in 1767, Black Hawk said the Sauk and Fox people never ceded their homeland and disagreed with Keokuk giving it up so easily. Black Hawk and others refused to leave unless forced out. Settlers obliged by destroying their crops and burial grounds.[3] Lacking sufficient support to push back, Black Hawk and the remaining Sauk and Fox people reluctantly moved west. In 1831, Black Hawk led a group back to their home for the summer as they had always done, but was persuaded to go back to Iowa Territory.

On April 6, 1832, Black Hawk again traveled east across the Mississippi River into Illinois. He thought this time would be different because he was led to believe he would get support from the British military and other Native American tribes still living in the area, particularly the Winnebago. Also, most of his band consisted of elderly, women, and children. Who would consider them a threat and attack them? Black Hawk’s band totaled about 1,000 people.

Around April 20th, Black Hawk’s group reached the Winnebago village, Prophet’s Town, along the Rock River. Once there, the Winnebago chiefs told him they couldn’t stay. They feared the U.S. Army and state militia would attack them if they provided aid, or allowed Black Hawk’s people to reside in their village. Black Hawk also learned no British aid would be coming. The group traveled northwest to a Pottawatomi village hoping to get some food, but again was turned away. Starving and unable to find support, Black Hawk decided to turn back down the Rock River toward the Mississippi River and the Iowa Territory in mid-May.

Black Hawk’s movements stirred the United States Army and Illinois Governor John Reynolds to action. Whereas U.S. Army General Henry Atkinson took a more measured approach initially, Governor Reynolds did not. A year before, Reynolds intended to mobilize the militia “to remove them [Native Americans] dead, or alive over to the west side of the Mississippi.”[4] In a July 1831 letter to the U.S. Secretary of War, Reynolds wrote, “If I am again compelled to call on the Militia of this State, I will place in the field such a force as will exterminate all Indians, who will not let us alone.”[5]

On his return trip back to Iowa, Black Hawk became aware of a nearby contingent of 200 – 300 Illinois militiamen led by Major Isaiah Stillman. Black Hawk sent three warriors under a white flag of truce to meet the militia and initiate a meeting to discuss the band’s peaceful travel back to Iowa. Scouts followed the warriors to observe the interaction in case things went awry.

Things went awry.

Stillman’s militia had received a double ration of whiskey in their search for Black Hawk and were drunk when Black Hawk’s men met them.[6] Stillman’s men shot and killed two of the messengers on the spot and began a pursuit of the observers back to Black Hawk’s camp. Most of his warriors were out hunting, but 40 men defended against the militia’s onslaught. Vastly outnumbered, Black Hawk’s band dispelled the militia with ease. The militiamen panicked and fled all the way back to Dixon’s Ferry. When they reached Dixon’s Ferry, 53 men were missing and thought to be dead. In truth, 11 had been killed by Black Hawk’s men during the fight the militia had instigated and 42 others deserted and went back to their homes. Black Hawk lost three men. Most of those initial militiamen refused to extend their service beyond their 30-day enlistment.[7]

This skirmish became known as the Battle of Stillman’s Run and it ended any chance for Black Hawk’s peaceful return to the Iowa Territory.

Forting Up & Call to Arms

Unable to travel southwest down Rock River, where armed militias were located, Black Hawk led his people north to find a safe path west across the Mississippi River. He needed to protect the large contingent of women, children, and elderly. Their best chance was to use their superior knowledge of the landscape to evade militias and soldiers that began hunting them.

Meanwhile, white people panicked. Governor Reynolds “not only calls for volunteers, but whips the entire state into a veritable panic by depicting this as an armed invasion by a hostile Indian force,” said John Hall, University of Wisconsin professor of history.[8] “Anglo-Americans living in frontier regions of the United States in this era were prone to panic at the slightest rumor of Indian hostilities and they themselves were prone to violent overreaction.”

And overreact they did. The panic spread rapidly into Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana. Groups of white settlers assembled and held rousing calls-to-arm. They invoked patriotism, formed poorly organized militias, and developed plans for defense against Black Hawk’s invasion that was never planned, never coming, and never arrived.

Henry Little, who lived on Gull Prairie near Kalamazoo, Michigan, wrote, “many of the people were wild and frantic with the insane excitement, and some were almost dying with fear, because behind every waving bush and tree their fruitful imaginations had pictured an Indian with an uplifted tomahawk.”[9]

Mark Wyman wrote, “Settlers rushed to ‘fort up.’ In the mining district stockades were quickly erected in Mineral Point, Dodge’s Diggins, Blue Mounds, Hamilton’s, Gratiot’s, White Oak Springs, Elk Grove, Diamond Grove and other spots.”[10]

In LaPorte County, Indiana, under the direction of Peter White, men gathered and built a stockade fort on the Door Village prairie to protect against the imaginary invasion.2In March 2024, the LaPorte County Commissioners named a bridge after Peter White for his fort-building heroics.

Not everyone was fooled. In Gull Prairie, a messenger delivered the word of coming Native American attacks. Men were called up to join the war to defend Gull Prairie. Of the brouhaha, Henry Little wrote, “I did not propose to go or in any way be a participant in the affair further than being a spectator, because I considered those sensational reports as being altogether too unreliable to be entitled to one moment’s serious consideration and too preposterous for any sane man’s belief.”[11]

In LaPorte County near Door Village lived Jean Baptiste Chandonnai. He had lived and traveled throughout Lake Michigan and Lake Huron and had experience working with Native Americans. One story told that General Joseph Orr asked him if he thought Black Hawk would come to LaPorte County. Chandonnai told him, No.[12] He did not help build the fort and surely did not seek safety inside its hastily built walls either.

In neighboring St. Joseph County, a stockade fort was constructed in Olive Township, but never completed.3In Goshen, Indiana, construction of Fort Beane started, but apparently was never finished. Beane’s descendants erected a large stone monument to memorialize its presence anyway. The monument still stands on Lincolnway East. Shortly thereafter, locals removed the palisades for firewood.[14] Daniel Green (Green Township is named after his family) told this story about the Black Hawk scare: “My brother, Nathan, and cousin, then at work on Sumption prairie putting out the crop at the future home, kept our people more correctly informed about the Indian war scare, and when they returned the first of August were able to relieve much of the anxiety of the colony as to the danger to life or otherwise from the Indians.”[15]

In Lagrange County, Indiana, panicked white settlers raced to Cedar Lake and began to fell trees to build a fort. Weston Godspeed wrote, “Many very interesting incidents occurred, but, within a day or two, the delusion was dispelled. The logs cut for ‘Fort Donaldson’ remained at the spot for many years.”[16]

In addition to hastily built forts, hastily assembled militias formed. One U.S. Army officer described state militias as, “that prosopopoeia of weakness, waste, and confusion.”[17] The assembled Gull Prairie militia marched around the wilderness searching for hostile Native Americans. The only skirmish they experienced was when two men fought over who should carry a rifle they had borrowed from another man. Ironically, most inhabitants of that area were Potawatomi and white residents of nearby Prairie Ronde “stood in so great fear of them that they did not consider themselves safe until they had deprived the fifteen or twenty Indians living on or near that prairie of their rifles. . . It is probable that the whites would not have submitted to such treatment as peaceably as did the Indians,” wrote Little. [18]

In Tippecanoe County, Indiana, “Over 300 old men, women, and children flocked precipitately to Lafayette and the surrounding country east of the Wabash,” wrote D.D. Banta.[19] “Lafayette literally boiled over with people and patriotism. A meeting was held at the court-house, speeches were made by patriotic individuals, and to allay the fears of the women an armed police was immediately ordered, to be called the ‘Lafayette Guards.’”

With full patriotic fanfare, the people sent off 300 militia volunteers to find and kill hostile Native Americans. The band of men found none and two weeks later decided to return home, whereupon they suffered their only casualty—while on night watch, one guard named Cox, shot another guard named Fox and fractured his thigh bone.

Tragedy to Massacre

While pioneers pumped patriotic bravado, the U.S. Army and militias hunted Black Hawk and his people. Many of the Sauk and Fox died of hunger, exhaustion, and violence. After six weeks, the survivors of Black Hawk’s band finally reached the Mississippi River. However, few would reach the Iowa Territory alive.

The Northern Illinois University Digital Library summarized that final day as follows:

Before dawn on August 2, the Battle of Bad Axe began. . . The warriors continued to fight, hoping to allow time for more of the women and children to cross the river. Just as Atkinson’s troops pushed them back toward the river, the refueled Warrior [battleship] returned and began firing its cannon into them from behind.

The slaughter on the eastern bank of the [Mississippi] river continued for eight hours. The soldiers shot at anyone—man, woman, or child—who ran for cover or tried to swim across the river. They shot women who were swimming with children on their backs; they shot wounded swimmers who were almost certain to drown anyway. Other women and children were killed as they tried to surrender. The soldiers scalped most of the dead bodies. From the backs of some of the dead, they cut long strips of flesh for razor strops.

Of the roughly four hundred Native Americans at the battle, most were killed (though many of their bodies were never found), some escaped across the river, and a few were taken prisoner. Of the one-hundred-and-fifty or so who crossed the river on August 1 and 2, moreover, few survived for long. Sioux warriors, acting in support of the army, tracked down most of them within a few weeks. Sixty-eight scalps, many from women, and twenty-two Sauk and Fox prisoners were brought by the Sioux to Joseph M. Street, the federal agent for the Winnebagos at Prairie du Chien in late August.[20]

State and federal government officials used the panic surrounding Black Hawk to justify further mistreatment of all Native Americans. In 1838, the United States government and the State of Indiana rounded up Native Americans residing in Indiana, destroyed their homes, and forced them to march to Kansas. One-fifth of them died. It is known as the Trail of Death.

The History Museum (South Bend, Indiana) wrote, “The excitement caused by the Black Hawk War was the beginning of the downfall of Native American tribes in Indiana. Although these Indians were perfectly quiet and peaceful and had nothing to do with causing the Black Hawk War, the white settlers of Indiana could not get used to their presence in the community.”[21]

What We Need Is a Monument!

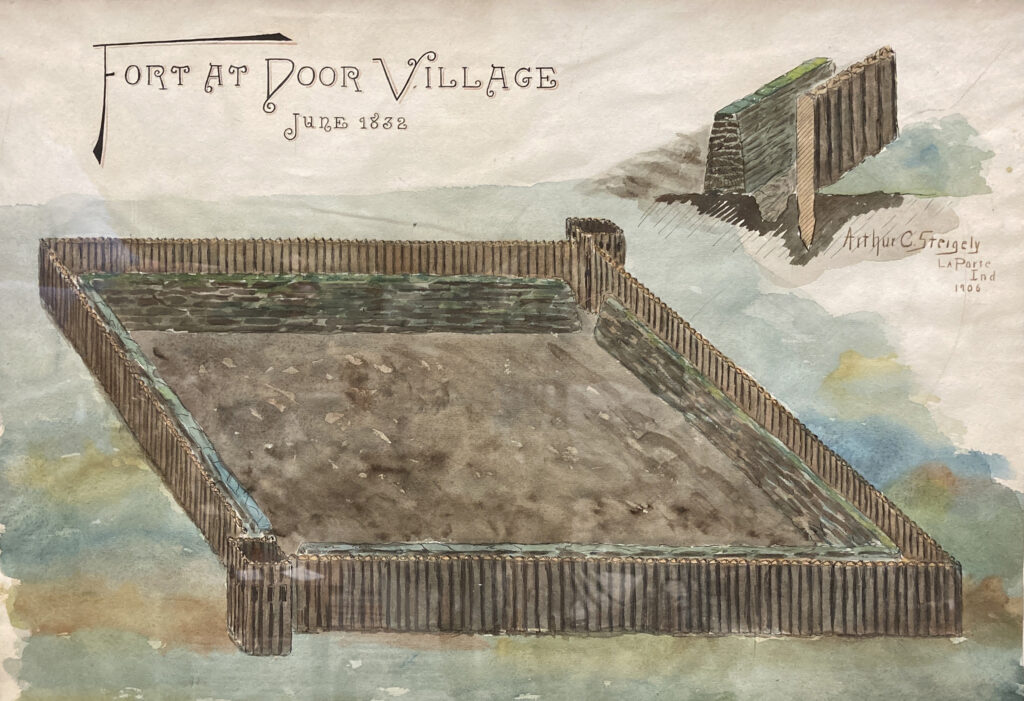

The turn of the Twentieth Century “was generally a period when Americans celebrated a mythical past of heroic pioneers,” wrote Dr. James Madison, professor of Indiana history.[22] Writers of history began to paint pioneers as noble, brave, and brilliant rather than the regular folks they were, who were prone to mistakes and bad decisions.4In 1906, a LaPorte artist, Arthur C. Steigely, painted a watercolor of the Door Village fort. Today, it hangs in the LaPorte County Museum. It is a funny drawing, but few people have gotten the humor. Steigely painted the moat inside the fort walls. In stockade fort construction, the dry moat was dug outside the wall. Then the dirt was piled up as a second barrier, followed by the palisade (log walls) erected to enclose the fort’s interior. Steigely could have gotten information about the fort from Robert White, who was then 96 years old and helped build the fort. If Steigely’s painting is accurate, the Door Village fort was built backwards. That wasn’t always the case.

The oldest-known written history of the Door Village fort appeared in 1874 in The LaPorte Chronicle published by Jasper Packard. Of the Black Hawk threat, Packard wrote, “The alarm proved, as is almost invariably the case, to have been greatly exaggerated.”

In 1880, C.C. Chapman & Company published “History of LaPorte County, Indiana” and told the story of the fort exactly as Packard had, including the words, “The alarm proved, as was almost always the case in those days, to have been greatly exaggerated.”

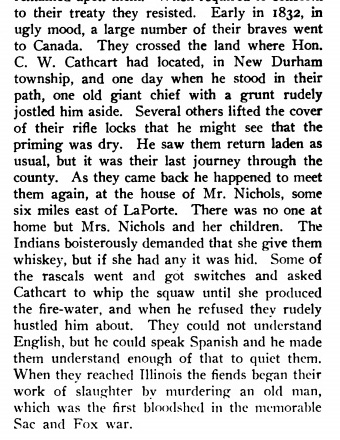

In 1904, E.D. Daniels flipped the script. In his book, “A Twentieth Century History and Biographical Record of LaPorte County, Indiana,” Daniels copied the history from Packard and Chapman, but deleted the sentence about the exaggerated alarm. Instead, he added these sensational lines, “Early in 1832, in an ugly mood, a large number of their braves went to Canada. They crossed the land where Hon. C.W. Cathcart had located, in New Durham township, and one day when he stood in their path, one old giant chief with a grunt rudely jostled him aside.” Describe another alleged incident, he wrote that Native Americans “boisterously demanded that [Mrs. Nichols] give them whiskey. . . Some of the rascals went and got switches and asked Cathcart to whip the squaw until she produced the fire-water. . . When they reached Illinois the fiends began their work of slaughter by murdering an old man, which was the first bloodshed in the memorable Sac and Fox [Black Hawk] war.”5Packard used a lot of oral history to assemble his 1876 book, “History of La Porte County, Indiana, and Its Townships, Towns and Cities,” which started with a series of articles in his newspaper based largely on interviews with older residents. Unfortunately, he never identified the sources of his oral histories. It’s valuable, but the oral history aspect must be kept in mind. Chapman copied a lot of Packard’s material and added pieces. He also included family history of people who may have paid for it (not uncommon at the time). Daniels copied material from Packard and Chapman and added embellishments and fiction. Readers should be skeptical of stories in Daniels’ book.

Historians knew exactly how the Black Hawk War started, yet Daniels got it very wrong. It is likely that everything Daniels wrote was false.6In the preface, E.D. Daniels wrote, “This is not a standard history. . . This is a work for the parlor table or drawing-room book case.” He also wrote that he “often adopted verbatim the very language of another as his own.” In short, he plagiarized largely from Packard and Chapman. Then he embellished many of the stories, and apparently added fiction to make the history more exciting. His book is the least reliable source of LaPorte County, Indiana, history. Furthermore, he disparaged Native Americans from cover-to-cover in his book. He wrote that no civilized people passed through LaPorte County until white people arrived (225), referred to Native Americans as savages (370) and red men (372), called their writing “rude hieroglyphics” (10), their agriculture practices imperfect, and that they were treacherous, thieves, and “were not as clean as might be in their habits” (11). He is not a reliable source, yet it is Daniels’ version of history that has dominated for 120 years.7If you encounter history that portrays virtuous pioneers defending themselves from savage Native Americans who attacked innocent settlers with impunity, it most likely is false. For decades, that fictional version of history was popularized by Western movies.

In 1910, the LaPorte Historical Society installed a monument to commemorate the builders of the Door Village fort. It consisted of a giant granite rock with two bronze plaques. One plaque features the names of the 42 men who supposedly built it. The other plaque reads, “On this spot a fort-stockade was built to defend the lives of the pioneers of LaPorte Prairie from a threatened invasion by Black Hawk and his braves in the spring of 1832. Warning of the danger was brought by John Coleman who rode his Indian pony Musquog from Ft. Dearborn to this place in six hours.” The source of that information is unknown. Although it has been repeated many times, nobody has verified its accuracy.

The monument dedication ceremony may have been an awkward event for those who paid attention. The LaPorte Historical Society tasked William Niles to research the Black Hawk War and present his findings. Reading from his paper, Niles acknowledged that no conflict with Native Americans occurred anywhere near LaPorte County, but that “the danger seemed very real and near.” Niles went on to say, “Thinking that others may be as ill-informed about the war and as much interested as I was, I have taken some account of those events from those sources, which are all in substantial agreement.” He then proceeded to recount the inglorious history of the Black Hawk War—the militia’s violation of a white flag of truce, how conflict could have and should have been avoided, and that it concluded with soldiers and militiamen massacring hundreds of Native Americans including many women and children along the Mississippi River. The builders of the Door Village fort did not defend against a possible Native American attack any more than people of New York City defended against a Martian attack in 1938.8The “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast caused some people to panic thinking it was real. That panic, like the threat to Door Village Prairie in 1832, was greatly exaggerated.

Subsequent generations did not heed Niles’ words. Instead, the history has been shaped by the words of E.D. Daniels and the inscription on those bronze plaques on that giant hunk of granite. Once someone erects a monument, installs a bronze plaque, or memorializes a structure with a name, it is difficult to get the story corrected. In the words of Mark Twain, “How easy it is to make people believe a lie and hard it is to undo that work again.”

Why It Matters

So, we have a monument that celebrates men who built a fort to defend against an attack that was never planned, never threatened, and never happened. The hastily-built fort was conceived in fear based on misinformation and scorn for Native Americans. The overreaction to Black Hawk’s movements led to the Trail of Death. History was whitewashed and truth suppressed. For 120 years we have been taught a fictionalized history that portrayed Native Americans as evil and pioneers as heroes who fended them off. Some knew better then and we all know better now.

The benefit of history is hindsight and viewing history through that lens enables us to learn from our mistakes. Can you think of a recent event in which people succumbed to fear, or anger, based on misinformation and unfamiliarity with different people? Rather than allow ourselves to get whipped into a panic, imagine if we had the understanding of our history to pause and think, “This reminds me of those pioneers who built a fort in 1832 to fend off Native Americans that weren’t a threat. Maybe we should think about this. . .” Cooler heads could prevail and better decisions would be made.

To have any hope to learn from our past, we must tell history honestly. As the adage goes, those who forget the past are destined to repeat it.

Further Reading

Chapman, C.C. & Company. “History of La Porte County, Indiana,” (Chicago, C.C. Chapman, 1880). https://www.loc.gov/item/rc01001660/

Gratzol, Abigail, “The Journey of a People: The Potawatomi of Indiana After the Trail of Death.” Thesis, (University of Indianapolis, 2023). https://www.in.gov/history/files/Gratzol-Bennet-Tinsley-2024-PAPER.pdf

Moss, Walter G., “The Pioneers: Heroic Settlers or Indian Killers?” History News Network, 2/2/2020, https://www.historynewsnetwork.org/article/the-pioneers-heroic-settlers-or-indian-killers.

National Geographic, “The United States Government’s Relationship with Native Americans,” https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/united-states-governments-relationship-native-americans/.

Packard, Jasper. “History of La Porte County, Indiana, and Its Townships, Towns and Cities,” (LaPorte, Ind., S.E. Taylor & Company, 1876). https://www.loc.gov/item/rc01001661/

White, John H., Dr., “The Black Hawk War in Wisconsin” (lecture, Wisconsin Historical Museum, Madison, Wisconsin, July 26, 2016). https://www.pbs.org/video/the-black-hawk-war-in-wisconsin-2zk5il/

Woodard, Colin. “How the Myth of the American Frontier Got Its Start.” Smithsonian Magazine, January/February 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-myth-american-frontier-got-start-180981310/

“The Black Hawk War of 1832,” Northern Illinois University Digital Library, https://digital.lib.niu.edu/illinois/lincoln/topics/blackhawk/background.

Bibliography

[1] Wyman, Mark. The Wisconsin Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 146.

“The outbreak was created from many strands, including white pressure on lands, and Indian resistance; tribal divisions, and strife between tribes. But the major cause of the Black Hawk War was the long-term buildup of fear and hatred between Indians and whites along the Mississippi.”

[2] Wyman, 148.

[3] “Black Hawk: Leader and warrior of the Sauk Indians,” Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed 4/14/2024, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1630. Also, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Dictionary of Wisconsin Biography (Milwaukee: North American Press, 1960), 37.

[4] Weitzel, Mikhael Sr., Misunderstandings to Massacres: The Black Hawk War of 1832, (US Army Sustainment Command, 2008), 43.

[5] “The Black Hawk War of 1832,” Northern Illinois University Digital Library, accessed 4/10/2024, https://digital.lib.niu.edu/illinois/lincoln/topics/blackhawk/background.

[6] Weitzel, 50.

[7] White, John H., Dr., “The Black Hawk War in Wisconsin” (lecture, Wisconsin Historical Museum, Madison, Wisconsin, July 26, 2016).

[8] White, John H., Dr.

[9] Little, Henry. “A History of the Black Hawk War of 1832,” Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan, vol. 5, (Lansing: W.S. George & Co, State Printers & Binders, 1884), 168.

[10] Wyman, 150.

[11] Little, 152-153.

[12] Packard, Jasper, History of LaPorte County, Indiana, and Its Townships, Towns and Cities (LaPorte: S.E. Taylor & Company, Steam Printers, 1876), 60.

[13] In Goshen, Indiana, construction of Fort Beane started, but apparently was never finished. Beane’s descendants erected a large stone monument to memorialize its presence anyway. The monument still stands on Lincolnway East.

[14] Howard, Timothy Edward. “A History of St. Joseph County, Indiana, Volume 1” (Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company), 300.

[15] Howard, 142.

[16] Godspeed, Weston A., Counties of LaGrange and Noble Indiana: Historical and Biographical (Chicago: F.A. Battey & Co.,1882), 225.

[17] White, John H., Dr.

[18] Little, 156.

[19] Banta, D.D., History of Johnson County, Indiana (Chicago: Brant & Fuller, 1888), 127.

[20] “The Black Hawk War of 1832,” Northern Illinois University Digital Library, accessed 4/10/2024, https://digital.lib.niu.edu/illinois/lincoln/topics/blackhawk/phases, accessed.

[21] “The Potawatomi Trail of Death,” The History Museum, accessed 4/10/2024, https://www.historymuseumsb.org/the-trail-of-death/.

[22] E-mail correspondence between James Madison and Matt Werner, 4/15/2024. To learn more about this era and its effect on history research, look up “Turner’s Frontier Thesis.”

[23] In 1906, a LaPorte artist, Arthur C. Steigely, painted a watercolor of the Door Village fort. Today, it hangs in the LaPorte County Museum. It is a funny drawing, but few people have gotten the humor. Steigely painted the moat inside the fort walls. In stockade fort construction, the dry moat was dug outside the wall. Then the dirt was piled up as a second barrier, followed by the palisade (log walls) erected to enclose the fort’s interior. Steigely could have gotten information about the fort from Robert White, who was then 96 years old and helped build the fort. If Steigely’s painting is accurate, the Door Village fort was built backwards.

[24] Packard used a lot of oral history to assemble his 1876 book, “History of La Porte County, Indiana, and Its Townships, Towns and Cities,” which started with a series of articles in his newspaper based largely on interviews with older residents. Unfortunately, he never identified the sources of his oral histories. It’s valuable, but the oral history aspect must be kept in mind. Chapman copied a lot of Packard’s material and added pieces. He also included family history of people who may have paid for it (not uncommon at the time). Daniels copied material from Packard and Chapman and added embellishments and fiction. Readers should be skeptical of stories in Daniels’ book.

[25] In the preface, E.D. Daniels wrote, “This is not a standard history. . . This is a work for the parlor table or drawing-room book case.” He also wrote that he “often adopted verbatim the very language of another as his own.” In short, he plagiarized largely from Packard and Chapman. Then he embellished many of the stories, and apparently added fiction to make the history more exciting. His book is the least reliable source of LaPorte County, Indiana, history.

[26] If you encounter history that portrays virtuous pioneers defending themselves from savage Native Americans who attacked innocent settlers with impunity, it most likely is false. For decades, that fictional version of history was popularized by Western movies.

[27] The “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast caused some people to panic thinking it was real. That panic, like the threat to Door Village Prairie in 1832, was greatly exaggerated.

NOTES

- 1Wyman, Mark. The Wisconsin Frontier (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 146. “The outbreak was created from many strands, including white pressure on lands, and Indian resistance; tribal divisions, and strife between tribes. But the major cause of the Black Hawk War was the long-term buildup of fear and hatred between Indians and whites along the Mississippi.”

- 2In March 2024, the LaPorte County Commissioners named a bridge after Peter White for his fort-building heroics.

- 3In Goshen, Indiana, construction of Fort Beane started, but apparently was never finished. Beane’s descendants erected a large stone monument to memorialize its presence anyway. The monument still stands on Lincolnway East.

- 4In 1906, a LaPorte artist, Arthur C. Steigely, painted a watercolor of the Door Village fort. Today, it hangs in the LaPorte County Museum. It is a funny drawing, but few people have gotten the humor. Steigely painted the moat inside the fort walls. In stockade fort construction, the dry moat was dug outside the wall. Then the dirt was piled up as a second barrier, followed by the palisade (log walls) erected to enclose the fort’s interior. Steigely could have gotten information about the fort from Robert White, who was then 96 years old and helped build the fort. If Steigely’s painting is accurate, the Door Village fort was built backwards.

- 5Packard used a lot of oral history to assemble his 1876 book, “History of La Porte County, Indiana, and Its Townships, Towns and Cities,” which started with a series of articles in his newspaper based largely on interviews with older residents. Unfortunately, he never identified the sources of his oral histories. It’s valuable, but the oral history aspect must be kept in mind. Chapman copied a lot of Packard’s material and added pieces. He also included family history of people who may have paid for it (not uncommon at the time). Daniels copied material from Packard and Chapman and added embellishments and fiction. Readers should be skeptical of stories in Daniels’ book.

- 6In the preface, E.D. Daniels wrote, “This is not a standard history. . . This is a work for the parlor table or drawing-room book case.” He also wrote that he “often adopted verbatim the very language of another as his own.” In short, he plagiarized largely from Packard and Chapman. Then he embellished many of the stories, and apparently added fiction to make the history more exciting. His book is the least reliable source of LaPorte County, Indiana, history.

- 7If you encounter history that portrays virtuous pioneers defending themselves from savage Native Americans who attacked innocent settlers with impunity, it most likely is false. For decades, that fictional version of history was popularized by Western movies.

- 8The “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast caused some people to panic thinking it was real. That panic, like the threat to Door Village Prairie in 1832, was greatly exaggerated.