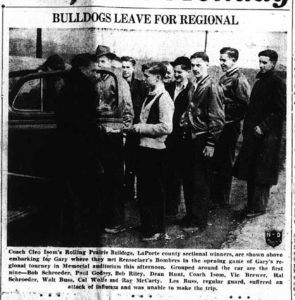

Foot after foot of microfilm spun off one reel and wound onto another reel. Old newspaper pages scrolled across a computer screen while my index finger held down the computer mouse button until I found the first week of March 1941. I slowed the reels and scanned for mentions of the Rolling Prairie Bulldogs. Five days of newspapers were missing, but the sixth day revealed a valuable image—a group of boys standing next to a sedan with its door held open. The caption read, “Coach Cleo Isom’s Rolling Prairie Bulldogs, LaPorte county sectional winners, are show above embarking for Gary where they met Rensselaer’s Bombers in the opening game of Gary’s regional tourney in Memorial auditorium this afternoon.”

The photo was a blotted mess, typical of microfilm images. Boy, it’d be something if I could find the original photo negative, I thought. I had access to a box of photo negatives that might’ve held it, but none of the film was marked and some well-intending, but misguided, person attempted to organize them by subject, rather than leave them in chronological order. I dug and sorted one envelope after another. I dumped a fat stack of negatives from an envelope titled, “Transportation.” I flipped through them, one by one, holding each one up to a light. And there it was—Cleo Isom’s Bulldogs.

Digital media is king. We upload music, stream videos, and take photographs with microcomputers. We copy, edit, save, delete and share in a flash. It is more efficient than the old system. Real film, that plastic medium with a silver gelatin finish required work. Loading film into a camera in the dark, unloading the film in the dark, applying chemicals to develop the film, washing film, drying film, working in a dark room with a red light, applying more chemicals to paper to develop a photograph. The process required skill and time. In the right hands, it created amazing images and analog film has something digital photography does not—connectivity.

When I found the photo negative from March 8, 1941, it was a great moment. Eureka! I’d found it. As I held it up to the light, balanced between my fingers, I became aware of something meaningful: this 4” x 5” plastic film—it was there!

This film traveled in the photographer’s car to Rolling Prairie, Indiana. It was on that dirt road while the photographer shook hands with the coach, talked to the boys, and told them where to stand. It was an inch away from the cameraman’s finger. It waited prone in the camera as the boys posed a few feet away. The shutter opened—click—and the boys faces shone upon the film’s silver gelatin, burning their image onto its surface.

The boys are dead now. The photographer is gone too. The car, the uniforms, the clothes—all gone. But this film survives and it was there. It met those boys, captured their moment, and here I am, holding it in my fingers.