Dave Greer and I sat in his basement drinking coffee. Behind him was a wall covered with trophies: bowling trophies won by his wife, Vivian, his son and daughter’s awards from Rogers High School, a color silhouette of Greer in a basketball uniform. The largest one recognized Greer as an outstanding scholar-athlete at Elston High School.

Greer remembered the night he became the first area player to shoot a jump shot in a varsity basketball game. It was 1953 and many people considered a one-handed jump shot showboating. It was an away game at an all-white school.

“They called me all kind of negative names,” Greer said. “They called me everything but God. We were the only black thing in there,” referring to himself and teammates Bill Wright and Braelon Donaldson. “The word — never heard it so many times in one day.”

The racial slurs rolled off Greer like heavy rain. He’d heard it before. The heckling drove him to play even harder. Take that! Keep scoring. Keep rebounding. Keep fouling (he fouled out that night). The Red Devils won by twenty-one points. After the game, the boys on the team showered, dressed and waited until everyone was ready. Then, they exited the locker room together, walked out of the school building, and boarded the bus as a group. Trouble didn’t occur, but they never took chances.

But all of it — the awards, the basketball, the winning, the education — just as easily might not have happened for a kid from the segregated neighborhood called The Patch. Greer and Bill Wright, his cousin and teammate, were two of the first black men to play varsity basketball in Michigan City, Indiana. Their stories extend beyond sports.

In the first half of the 20th century, if you were black and lived in Michigan City, there was a good chance you lived in The Patch. With few exceptions, it was the only housing available to your family. Centered on Fourth Street and locked in by Michigan Boulevard on the west and Trail Creek on the east, eighty-eight families squeezed onto a five acre dirt patch crowded with houses and apartment buildings surrounded by factories.

“It was right near the railroad tracks by Blocksom Manufacturing, which used to bring in cow tails and so on,” Wright said. “There was a big stink back there, and the box cars used to come and pick up stuff or dump some of it off. We constantly heard trains going by, and we constantly had that smell back there behind The Patch.”

Average-sized homes, shanties, apartment buildings and large houses carved into smaller apartments packed the area. All of them were wood structures with faded paint, asphalt shingle siding, or weather-beaten wood siding. While some houses faced Michigan Boulevard or Fourth Street, most faced one of the alleys that crossed through The Patch. A few feet separated buildings and a makeshift courtyard filled the void between houses clustered in close proximity. As one resident descended the stairwell from a second-story apartment, they entered the courtyard and stared directly into their neighbor’s window. With only one city street running through The Patch, addresses were fractioned. One house on an alley was 4183/4 Fourth St. When a new house was squeezed between it and the one to the north, it had to become 4187/8 because there was no more room and no more numbers available.

Due to the volume of foot traffic racing through the cramped quarters, grass struggled to take root. The street was dirt, the alleys were dirt, the courtyards were dirt. On dry days, dust whirled between houses and wafted into open windows. On rainy days, mud caked everything.

For years, residents fought for better conditions and desegregation, but in the 1940s and 1950s, relief hadn’t arrived. Despite the rough exteriors, residents kept their indoor spaces tidy and clean, the common areas free of litter, trash deposited in wooden stalls. It was a proud community that looked out for one another.

“It was a normal life,” Greer said. “We knew our place.”

Knew our place.

“We knew how much liberty we had,” he explained. “As long as we were in our sector, we were OK. That was the way of life. Segregation. We knew our place and stayed in it.”

Greer recalled going to the movie theater where ushers indicated where he should sit. Two policemen stood near the entrance to ensure moviegoers followed those directions. “They’d tell you, ‘There are better seats up there,’ and you better go there or get put out!”

On the way to the movies and on the way back home, kids from The Patch had to pass through a white neighborhood. You arrived at your destination and you returned to The Patch. The kids knew not to linger.

Washington Park, with its carnival, picnic area and zoo, was open, but police squad cars parked behind one section of the Lake Michigan beach. Blacks were cordoned into a separate section where the water was deeper, an absurd arrangement considering many Patch residents hadn’t learned to swim.

“They had a section roped off. A rope. At the beach. And you couldn’t go outside that. Talk about segregation,” Greer said, shaking his head.

“Any time (the police) saw anybody slip away, they went down and straightened that out right away,” Wright said.

It seemed like a waste of time and resources for trivial leisurely activity, I said.

“To them, that wasn’t trivial,” Wright said. “That was the whole point. They thought it was a matter of life or death, so they put up this ring and then enforced it, too.”

Local restaurants were out of the question. The Hickory Pit with its Southern-inspired food and “chicken in the rough” was popular with Patch residents, but only served blacks at the back door. Carry-out only.

“If you wanted to get a soda or a milkshake, you could go into a place and get it, but you couldn’t sit down and drink it,” Wright said. “You couldn’t go into a restaurant unless it was a black restaurant, and there weren’t many of those. Not back in those days.”

Retailers allowed blacks to shop in stores, but maintained rules that kept Patch residents in their place.

“Department stores. You could buy things, but you couldn’t try on clothes. Not in the store. You could leave and bring them back, but you couldn’t try them on,” Wright said.

Despite the restricted liberties, children in The Patch played like any other kids. Summer mornings, boys played football in the sand dunes. By afternoon, they were playing baseball near the Pullman rail yard. But as the sun faded toward the horizon, they knew they had to be back in The Patch before dark.

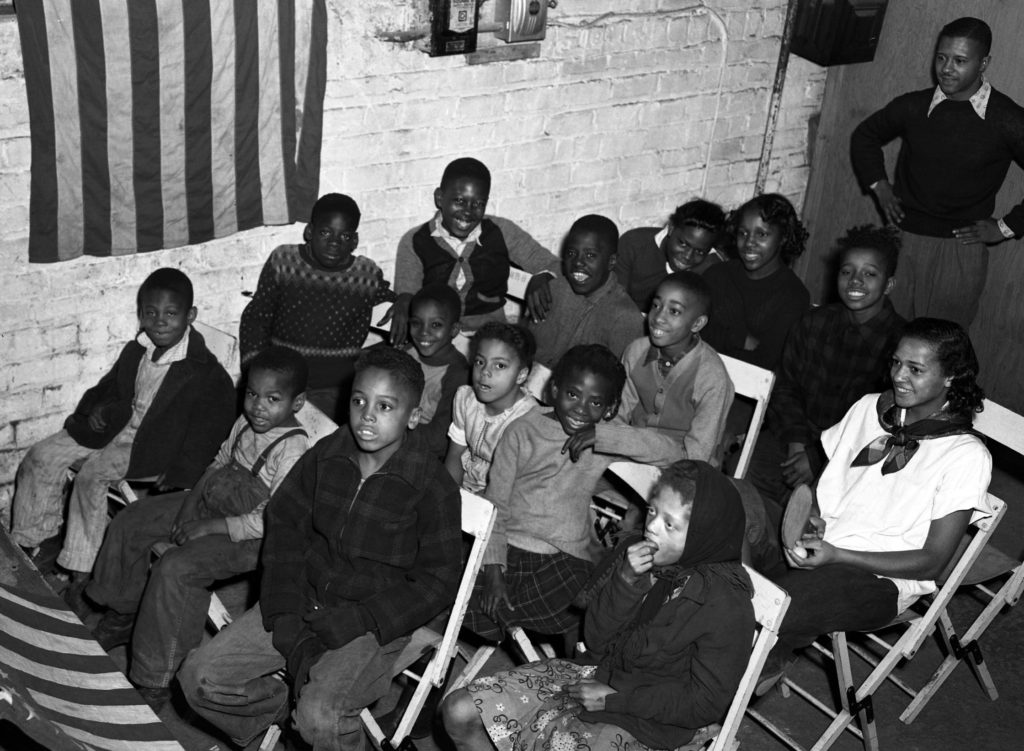

The Patch had a small grocery store, a barber shop, Sammie’s Tavern, Doc Adams’ bar room, an old hotel, a church and, most importantly, the Elite Youth Center. Elite (pronounced E – light) sat in the basement beneath the church on Michigan Boulevard. When the center opened its doors each evening, kids filled the basement rooms. There, they watched a TV someone donated, played ping-pong, shot billiards, socialized and played games. In the back of the church, beyond the wall behind the pulpit, was a small gymnasium. That was where Charlie Westcott taught the boys the game of basketball.

Westcott was born in Virginia and graduated high school in New Jersey. He briefly attended Johnson C. Smith University in North Carolina and served in the Coast Guard during World War II. Westcott moved to Michigan City with his wife, Marie, in 1947 to work in a local factory. When he arrived, he immediately volunteered at the Elite Youth Center.

“He’s the reason for all of us,” Greer said. “Charlie Westcott. He ran the Elite Center. A place where the kids could go at night for about four hours. It was under the church, and it had a gym in the back and we would faithfully go there every night. Every night. That’s where we learned to play ball. Every kid who went through the system came through him.”

“He was a very fine basketball player himself, very tricky guy, knew the game very well,” Wright said. “We all learned how to play basketball down there, and Charlie taught us all. By the time we left there, we were quite ready to play basketball at the public schools.”

Westcott divided the kids into five age levels: tiny tots, rinky dinks, intermediates, juniors, and seniors. Each group eagerly anticipated their chance to play in the tiny gym in back of the church and learn from Charlie. The youngest kids worked on dexterity drills—running forward and backward, cutting side to side, jumping and shooting a basket. The boys were divided into teams and ran through the drills relay-style, tagging the next kid in line to run through his drills and make a basket. The boys quickly learned to shoot because nobody wanted to let down their teammates and be the kid who couldn’t make a basket.

“Oh yeah. He taught us all how to play,” Greer said of Wescott. “He was kind of a trickster, go behind your back and stuff to get around somebody. He was a master. We worshiped him. Everybody loved him.”

Westcott taught the boys the game’s finer points. By the time they had the chance to play organized basketball in junior high or as freshmen, they had sound fundamentals and great skills.

Warren Jones—Michigan City Elston’s long-time teacher, principal, and administrator—coached the freshman basketball team in the 1950s and remembered Westcott well.

“He taught the boys a lot about how to play basketball,” Jones said. “When they came out for the (freshman) team, they knew a lot about what to do.”

In the early 1950s, Elston High School had good coaches. They included Jones, junior varsity coach Doug Adams and varsity coaches Dee Kohlmeier and Ick Osborne.

“When you have a Kohlmeier, an Osborne, a Warren Jones — those guys were a great fabric,” Wright said. “When I was in the ninth grade, I met Warren Jones and he took me under his wing and taught me basketball too. He taught me to appreciate the work-hard ethic: You go full steam all the time. He continued to watch me and instruct me. Dee Kohlmeier was the coach then, and he came and watched our practice and he had some instruction to give me too. He was extremely good.”

By 1950, the high school graduation rate in Indiana crept toward 60 percent, yet among Michigan City’s black community, it was closer to zero percent. When he arrived in town, Westcott’s first mission was to encourage kids from The Patch to value an education, to stay in school, and to graduate. While much of society was segregated, Michigan City schools were fully integrated — black kids had the same teachers as everyone else.

“That was an amazing thing,” Wright said. “That was the saving grace of that city for anybody who wasn’t white because you could get an education there that could send you on if you wanted it. That’s one of the great credits of Michigan City. If you’d been down in several other parts of the country, segregation was the rule and it could hurt you. A lot.”

In 1950-1951, five sophomores made the varsity basketball team led by Gene Burrell. Coach Kohlmeier recognized Burrell’s ability and cared less about the color of his skin. Burrell’s smooth movement and athleticism stunned local basketball fans.

“When Gene (Burrell) came on, they couldn’t believe a basketball player could move like that,” Wright said.

Burrell learned to play basketball at the Elite Youth Center. He became the first black basketball player to start at Elston High School and was the Red Devil’s second-leading scorer. But Burrell quit school after his sophomore year. Braelon Donaldson, his classmate, teammate, and fellow Elite Youth Center player, returned.

“He was the man,” Greer said of Donaldson. “He was a state high school pole vaulter. He went to IU and pole vaulted down there. He was a real nice dude. He was fortunate. He lived on the east side and his dad had a little car wash. In his senior year, his dad got him a car. And there were about ten of us who got in that car and went to school.”

Donaldson was a handsome young man and a gifted athlete. He won the state pole vault competition as a junior. He was the team’s second-leading scorer in 1952 and helped the team win Elston’s first Sectional championship in four years. That season, another promising young basketball talent arose from The Patch: Bill Wright.

“Then we had a good coach in Ick Osborne,” Wright said of the school’s new coach, who replaced Kohlmeier. “He was an extremely good man; he and his wife. He looked out for us. Back in those days, if you were black, you couldn’t even stay in the hotels. When we traveled, we couldn’t stay in the motels and hotels with the team. We always had to find a black family that would take us in, and that happened a number of times. There was nothing Ick could do about it. He was always outraged by it, but there was nothing he could do about it because that’s the way it was done. They weren’t allowing black folks to stay in hotels and motels.”

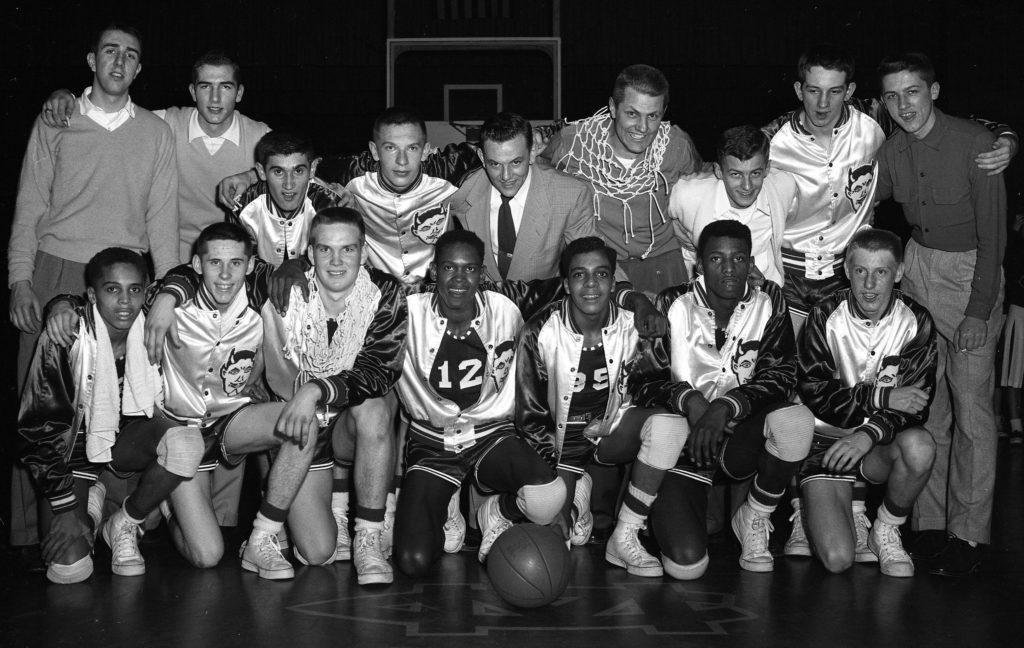

In 1953, Donaldson became the first black basketball player to lead Michigan City Elston in scoring. Wright was a starting guard and finished third in scoring. Michigan City won its second straight Sectional championship and finished the season 14-9.

Greer, a sophomore, moved up to varsity midway through the season and started a few games. That’s when he experimented with the jump shot.

“I saw it on TV. Guy from Michigan State. He was the only one (shooting a jump shot),” Greer said. “Nobody else was doing it. Nobody around here had ever seen anything like that.”

Greer began practicing his shot in the back of the church in The Patch and during practice in the Elston High School gym with Coach Osborne looking on. Osborne saw the advantage of a jump shot performed by a tall kid with good leaping ability, especially if that kid made more than he missed.

“He didn’t complain,” Greer said. “Then I did it in a game and almost got run out of the gym.”

That’s when opposing fans spat racial slurs at the black kid they perceived as trying to show them up. Their hate-filled yells aimed to put him back in his place, but they failed. Greer continued to develop his shot. Teammates and opposing players followed suit as the jump shot became the dominant shooting style.

Another player who developed into a fine jump shooter in the Elite Youth Center was Harlan Hunt. A tall, lanky, athletic kid, Hunt made the varsity basketball team in the 1953-54 season and provided the punch the Red Devils needed. Now three young men connected to The Patch started on the team: Wright at guard, Greer at forward, and Hunt at center. The team also got a boost from an unexpected Elite Youth Center player: Dick Cook.

Most families had minimal social interaction with the black community, but Cook and Greer became friends playing baseball and basketball together. Cook invited Greer to his house for dinner, and his parents gladly set another plate at the table.

“That was far from common,” Cook said.

Playing summer baseball, Cook got to know Westcott. When he heard about basketball being played in the back of the church in The Patch, he showed up to play. Many white kids were afraid to visit the Patch, but not Cook, Greer pointed out.

“He came down (to the Elite Youth Center). He was rough down there on the boards. He came down there and got better. Much better,” Greer said with a laugh.

“That was mostly in the dark,” Cook said, but “word got out and people began to talk. ‘Hey, Cook was down at the Elite Youth Center.’ So what? It was a place to play basketball. It’s not like there was a basket on every pole back then.”

His family ignored the gossip and rebuffed other peoples’ prejudice and fears. Their son was happy, having fun, and staying out of trouble. They had no problem with him spending his evenings in The Patch in the Elite Youth Center.

“That wasn’t the norm, that’s for sure,” Cook said.

Along with seniors Herb Sperling and Blake Waterhouse, the team had a strong nucleus and they still had Coach Osborne—a positive presence in the kids’ lives.

“Let me give you a story about Ick Osborne,” said Wright. “He invited us as a team over to his house once and his wife cooked a chicken dinner. Now Ick was a southern boy, southern Indiana, I think, and he had a very nice demeanor. But he understood one thing: if you’re going to serve chicken, people might be uncomfortable eating chicken—do I use a fork or a knife or not? So, he left all of the silverware off the table and we all ate with our fingers. That’s the way he was. He looked out for his people and he made them as comfortable as he could and he fought for their interests the best he could.”

Coach Osborne fought for his boys and in turn, the boys fought for him. The team didn’t hear much noise about three black kids in the starting lineup. In recent years, the Elston basketball teams had struggled to amass wins in a single season. The city was excited to have a winning team and the boys won game after game in convincing fashion, frequently beating opponents by twenty and thirty points.

“[Dave Greer] had a left-handed jumper,” said Indiana Basketball Hall of Famer, Bill Hahn. “Great ball player. I can see him shooting that jumper like it was yesterday. Wright was a helluva guard. Bill could really shoot. Those were really good ball players. Fun to watch.”

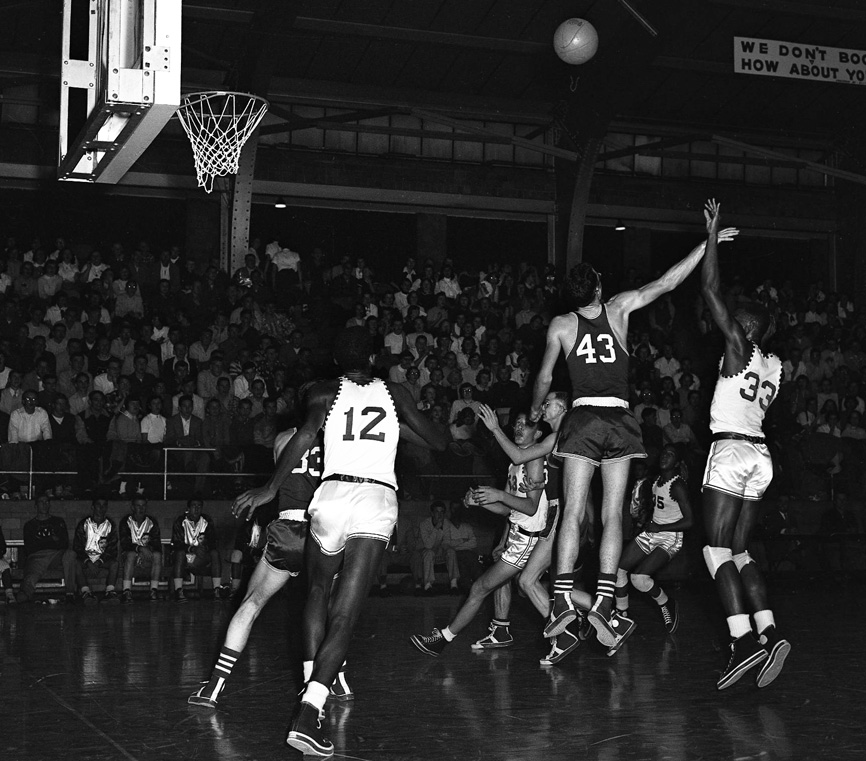

Michigan City residents’ love for basketball grew to a fever pitch. To accommodate the growing interest in basketball games, the school lined up rows of folding chairs between the grandstands and the playing floor. Shortly thereafter, it installed new bleachers in that space.

Tickets become a hot commodity. After winning its first twelve games, the Red Devils would host the 10-1 Elkhart Blue Blazers. The two teams were ranked second and third in the state. Elston gave Elkhart 400 tickets for the game, of which 109 became available to adults. Fans lined up at 4:30 a.m. in Elkhart in zero degree weather to buy a ticket. In Michigan City, residents formed a line a block long outside Beebe’s Sporting Goods store to buy a ticket. They sold out in thirty minutes.

By the time the game started, the auditorium was hot. Every seat was filled, some fans stood in the corners, and the place steamed with anticipation.

Michigan City trailed at halftime, 29 – 25, but the offense popped in the third quarter as Elston outscored Elkhart, 20 – 9, in the period. The boys never relinquished the lead. Wright and Greer led the team with fifteen points apiece. Dick Cook added fourteen more and Elston won, 67 – 61.

At 10:00 p.m. that night, the local newspaper got a phone call from Camp Atterbury in Indianapolis. The caller indicated there were five of them there from Michigan City and they wanted to know the score of the game. Michigan City Red Devils basketball had arrived.

The team improved its perfect record to 13-0 and moved up to number two in the state rankings. Being on a winning basketball team brought some changes.

“We were allowed to go places blacks weren’t allowed to go,” Greer said. “We could go inside the restaurants. There was one place we’d go after all of the away games—8th Street Café. They used to feed us there. Beforehand, we didn’t go there. No. You had to be a basketball player. No blacks went to any restaurants at that time. Huh-uh. That was the first time I went in, when I started playing basketball.”

But that was something Coach Osborne had arranged in advance after the team returned after a late-night away game (as Dee Kohlmeier also had done). Without the rest of the team, the boys from The Patch were still barred from sitting down and eating.

Hit Play to hear Bill Wright tell the following story about the M & M:

“M & M—a very popular place with the students and people in Eastport,” Wright said. “They wouldn’t allow any black people to sit down in the restaurant. One night some of the basketball players, we were trying to tell some of the white students who were following the team that there was this segregation, or exclusion, in town and they didn’t believe it. And there’s no reason they would have known it because they never saw black folks around anywhere—that was a normal thing. We took a couple of them out there once just to prove to them so they would understand what that problem was. We went in there and we were told to leave. And then the three people who went with us also left. They didn’t go back again for that matter.”

The Red Devils lost only two games during the regular season by a combined eight points. They breezed through the Sectional, winning three games by an average margin of thirty-two points. The team looked poised to win its first Regional championship since 1935, but right before the tournament, Dick Cook got sick.

“The famous mumps,” Cook said with a laugh.

The team squeaked into the Regional final without Cook in the lineup, but lost to Hammond High School in the championship game. The team finished the season 22-3. Michigan City would have to wait to win a Regional championship. They lost Bill Wright to graduation—he earned a basketball scholarship at the University of Michigan—but with Dick Cook, Dave Greer, and Harlan Hunt returning, fans eagerly anticipated the next season.

In 1955, the Red Devils continued their winning ways as Cook, Greer, Hunt, and Bill Wright’s younger brother, Jack, led the team. Mid-season, the all-black high school and basketball powerhouse, Indianapolis Attucks, starring Oscar Roberston, played the Elston Red Devils in Michigan City.

“I’ll never forget that,” said Cook. “During warmups the band was playing ‘Shake, Rattle, and Roll’ and each guy on their team dunked it—even the little guy, the little guard! Well, that shattered our confidence right there.”

Attucks won that game.

At the end of the season, Elston won its fourth straight Sectional championship and advanced to the Regional final where the team lost to Gary Roosevelt, another all-black high school, by seven points. Dick Cook became the first player in Red Devil history to score 500 points in a season and the team finished with a 20-6 record.

Two weeks later, Attucks and Roosevelt played for the State championship in Indianapolis. The contest guaranteed an all-black high school would win the State championship for the first time ever. Thinking about that game, a wide smile passed over Dave Greer’s face.

“Oh yeah. That was history. Yes, it was,” Greer said. “Should have been us there, but…”

His thought ended. The smile lingered.

O’Neil Simmons grew up in The Patch. He is eleven years younger than Dave Greer and he too experienced the segregated section of the movie theater. As time went by, attitudes began to shift. Slowly.

“We didn’t have to go through what Dave and Bill had to go through,” Simmons said. “Things got a little better.”

In 1960, the city tore down The Patch, but The Elite Youth Center remained. Simmons’ family moved to the east side of town. Whereas his old elementary school enrolled more black kids than white kids, his new classroom had two black kids: him and one girl. When sixth grade basketball tryouts started, Simmons left school and went to the Elite Center to play, just as he had always done. Westcott asked him when basketball began at the school.

“Tryouts started tonight,” Simmons said.

“What are you doing here then?” Westcott asked.

“I feel out of place. I don’t know any of them. I don’t want to play there.”

Westcott sat him down and explained the importance of moving beyond The Patch.

“Nobody is going to recognize you playing ball here in the Elite Center against small churches and other centers,” Westcott said. “If you want a shot at a college scholarship, you have to play organized basketball in the school.”

Simmons went back to the school, tried out, and made the team. Six years later, as Elston’s starting point guard, he helped Michigan City capture its first Indiana state basketball championship in 1966. In fact, half of that championship team had learned basketball from Charlie Westcott and had played at the Elite Youth Center.

From 1952 to 1975, Michigan City Elston basketball won twenty-four straight Sectional championships, seven Regional championships, one Semi-state and one State championship. The teams recorded 473 wins against 138 losses during that time. Many good kids and great basketball players made that happen.

Young men from The Patch and the Elite Youth Center were part of that success. They stood behind the rope at the beach, sat in a segregated section at the movie theater, got their food to-go, and spent their nights in a separate house when the basketball team traveled.

Those men endured injustice, yet their photographs graced the sports pages of area newspapers, sportswriters praised their accomplishments, and Michigan City residents stood in line to buy tickets to watch them play.

Sports are more than just games people play. Sports bring out the best and the worst in us. They are reflections of ourselves.

Those men endured injustice and Michigan City’s history is richer because of them.

© Matthew A. Werner